Agenda

Agenda

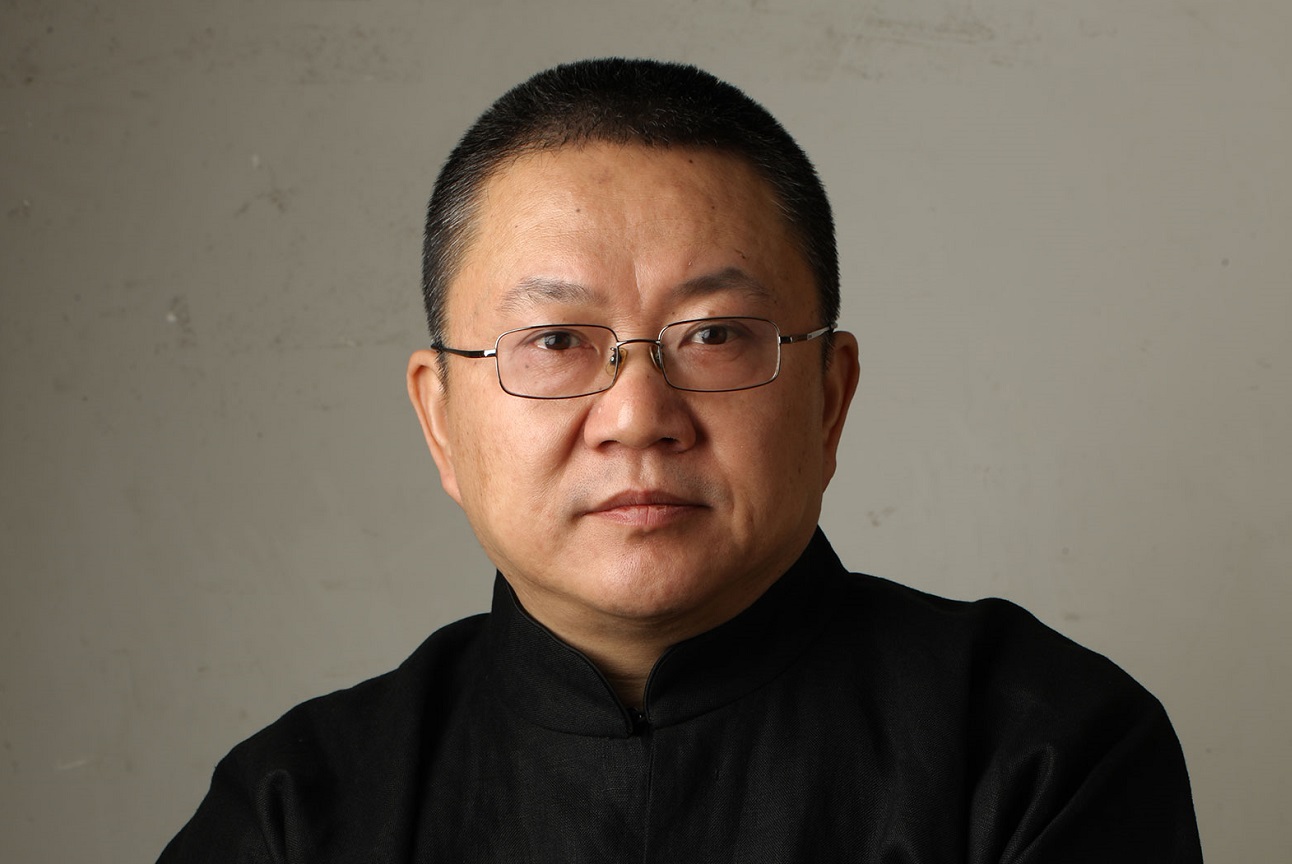

18:00 Lecture di Wang Shu

Introduce Matteo Ruta

Wang Shu, (born November 4, 1963, Ürümqi, Xinjiang, China), Chinese architect whose reuse of materials salvaged from demolition sites and thoughtful approach to setting and Chinese tradition revealed his opposition to modern China’s relentless urbanization. He was awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2012 for “producing an architecture that is timeless, deeply rooted in its context, and yet universal”.

Wang grew up in Ürümqi, the capital city of Xinjiang, China’s northwesternmost province. He studied architecture at Nanjing Institute of Technology (B.S., 1985; M.A., 1988). He then researched building restoration for the Zhejiang Academy of Fine Arts (now the China Academy of Art) in Hangzhou and, while there, completed his own first architectural project in 1990—a youth centre for nearby Haining.

Subsequently he embarked on an intensive study of construction practice and of the craftsmanship involved in building. In 1995 he began advanced studies at Tongji University (Ph.D., 2000). Two years later he and his wife, Lu Wenyu, together established a practice, Amateur Architecture Studio, in Hangzhou. From 2000 Wang Shu taught at the China Academy of Art and served as head of the architecture department, and in 2007 he became dean of the architecture school. In addition to designing the Library of Wenzheng College, Suzhou University (completed 2000), several houses (Sanhe House, Nanjing, 2003; Ceramic House, Jinhua Architecture Park, 2003–06; Five Scattered Houses, 2003–06), an apartment building (Vertical Courtyard Apartments, 2002–07), and more than 20 campus buildings for Xiangshan University (2002–07) in Hangzhou, Wang Shu designed several exhibition halls and pavilions as well as the Ningbo Contemporary Art Museum (completed 2005).

Perhaps his signature work is the Ningbo History Museum (completed 2008), which epitomizes his architectural philosophy. Like his other work, it incorporates local recycled materials—tiles, bricks, and stones—and combines modern technologies with traditional crafts and attention to the building’s site. It provided a striking contrast to the ultramodern structures of urban China, which he has described as “soulless.” During this period, Wang Shu also made the installation Tiled Garden (2006) for the Venice Biennale. The garden consisted of a sea of tens of thousands of tiles that had been salvaged from Chinese demolition sites, laid in meditative rows, and made accessible to the viewer by means of a bamboo bridge.

Wang Shu’s Pritzker Prize citation noted “the exceptional nature and quality of his executed work” and also “his ongoing commitment to pursuing an uncompromising, responsible architecture arising from a sense of specific culture and place”. Despite his growing popularity and fame as an architect, Wang Shu, who practiced calligraphy, considered himself a scholar, a craftsman, and an architect, in that order. He saw the abilities to adapt and to improvise as critical characteristics of the craftsman.